Book Excerpt

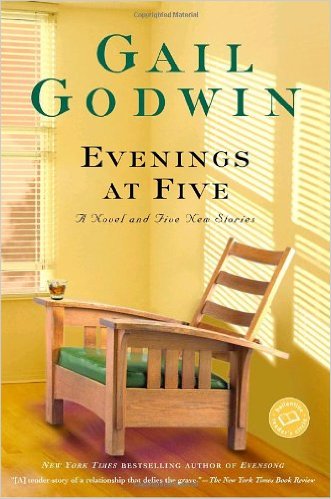

Evenings at Five

Evenings at Five

A Novel

Published 2003

Five o'clock sharp. "Ponctualité est la politesse des rois": Rudy quoting his late father, a factory owner (textiles) in Vienna before the Nazis came. The Pope's phone call, followed by the grinding of the ice, a growling, workmanlike sound, a lot like Rudy's own sound, compliments of the GE model Rudy had picked out fourteen years ago when they built this house. Gr-runnch, gr-runnch,

grr-rr-runnch. ("And look! It even has this tray you pull down to mix the drinks." Rudy retained the enthusiasms of childhood.) He built Christina's drink with loving precision after the Pope's call. Rudy did the high Polish voice, overlaid with an Italian accent: "Thees is John Paul. My cheeldren, eet is cocktail time."

Or sometimes Christina's study phone would not ring. Rudy simply emerged from his studio below and called brusquely up to her in his basso profundo: "Hello? The Pope just called. Are you ready for a drink?"

The ominous rolled r's on the "ready" and "drink": if you're not, you'd better be. I won't be here forever, you know.

The cavalier slosh of Bombay Sapphire (Rudy never measured) over the ice shards. The fssst as he loosened the seltzer cap and added the self-respecting splash that made her able to call it a gin and soda. Then, marching over to the sink: "I need Ralph." Ralph was their best serrated knife. The thinly cut slice of lime oozed fresh juice. Rudy cut well; he cut his own music paper, and he had been cutting Christina's hair exactly as she liked it for twenty-eight years. And in summer, a sprig of mint from the garden, a hairy, pungent variety given to them by the wife of a pianist who had recorded Rudy's music. Sometimes Rudy joined Christina in the gin and soda. Her financial man from Buffalo had given them two twelve-ounce tumblers with old-fashioned ticker tapes etched into the surfaces. She always kept them in the freezer, so they would frost up as soon as they hit the air.

Other times Rudy would say, "I need a Scotch tonight." That went into a different glass, a lovely cordial shape etched with grapes, given to him by the daughter of a pasha who had invited him to her houseboat parties in Cairo back in '42 and called him Harpo because his assignment in the Royal Air Force had been playing piano and harp to keep up troop morale. "I need a Scotch tonight" could mean either that his work had gone extremely well or that some unwelcome aspect of reality (his music publisher sending back sloppily edited orchestra parts, being put on hold by his health insurance provider, being put on hold by anyone at all) had undermined his creative momentum.

"Thees is Il Papa calling from the Vatican. Cheeldren, eet is cocktail time."

Christina was a cradle Episcopalian who had gone to a Catholic school run by a French order of nuns in North Carolina. Rudy was a nonpracticing Jew who had gone to a Catholic Gymnasium in Vienna until age fourteen, when the Nazis came. Rudy always liked to tell how there were two Jews and one Protestant in his class at the Gymnasium, "and the Protestant had the worst of it by far." So Rudy and Christina shared an affectionate fascination with Popes, especially this one, with his hulking masculine shoulders before they began to stoop, and his nonstop traveling, and all the languages.

What did I think, that we had forever? Christina asked herself, sipping the gin and soda she now made for herself. Often Rudy had interrupted himself in midsentence to explode at her: "You're not listening!"

What was I listening to? The ups and downs of my own day's momentum. We were both "ah-tists," as the real estate lady who sold us our first house pronounced it. She herself had been married to an ah-tist. Her husband's novel had been runner-up for the Pulitzer, she told us, the year Anthony Adverse won. Her name was Odette, as in Swann's downfall. Rudy was fifty-two and I was thirty-nine and neither of us knew, until Odette carefully explained it to us, that you could buy a house without having all the money to pay for it up front.

Christina would arrange herself on the black leather sofa they had splurged on in their midlife prosperity (a combined windfall of a bequest from Rudy's late uncle in Lugano, with whom Rudy had played chess, and a lucrative two-book contract for Christina, in those bygone days when there were enough competing publishers to run up the auction bid) and which the Siamese cats had ruined within six months. She would cross her ankles on the Turkish cushions on top of the burled-wood coffee table and train her myopic gaze on Rudy's long craggy face and crest of white hair floating reassuringly from his Stickley armchair on the other side of the fireplace. An editor had once told Rudy he looked like "a happy Beckett." Christina felt rich in her bounty: the workday was over and she had this powerful companion pulsing his attention at her, and her whole drink to go. They raised their cocktail glasses to each other.

Ballantine Books | Paperback| 320 pages